Across the Atlantic 1901-1976 ~ A 75th Anniversary

By Maurice Chaplin

Published in The Cat's Whisker, v.6-n.4, December 1976

This month marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of Marconi's successful trans-Atlantic experiment and is an appropriate time to review how it was accomplished.

By 1900, the 26 year old Marconi had proven to his own satisfaction that the earth's curvature did not interfere with radio propagation of distances up to 100 miles and that the time was ripe for long distance tests which, if successful, would be of considerable commercial value to both the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Co. Ltd., and the recently formed Marconi International Marine Communication Co. His fellow directors, already committed to heavy capital expenditure reluctantly consented to the raising of further large amounts of money to be risked in the attempt to establish trans-Atlantic communication between the United States and England.

Cape Cod was chosen as the area for a transmitting and receiving site in the U.S. In England, a lonely spot, high above the cliffs on the South Coast of Cornwall, named Poldhu, was chosen because its remoteness ensured privacy. Work began at this site in October, 1900.

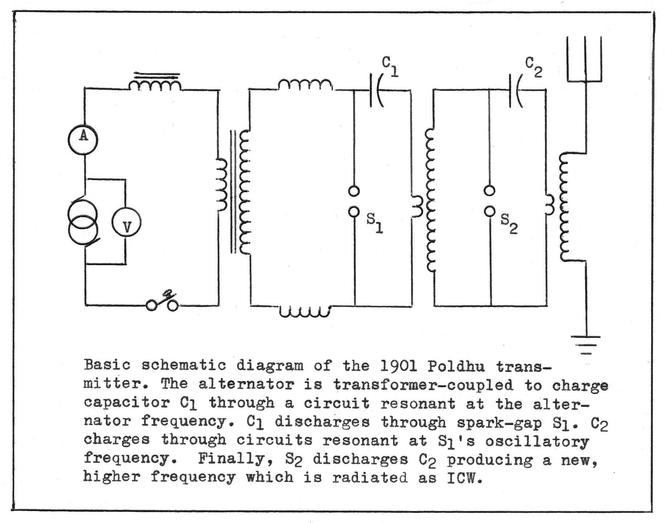

It was realised that a transmitter far more powerful than any previously built must be used and Prof. J.A. Fleming, the consultant engineer retained by the Marconi Co., began the preliminary design. A 32 h.p. oil engine drove a 25kW 50Hz Mathew and Platt alternator. The 2Kv alternator output was stepped up to 20Kv and a capacitor spark-gap combination produced an intermediate frequency. A second transformer, spark-gap, capacitor combination resonated at this intermediate frequency, and the new frequency produced at the second spark-gap was radiated.

The antenna consisted of an inverted cone supported by 20 masts each about 200 feet in height, arranged in a circle roughly 200 feet in diameter. A similar antenna was erected at the Cape Cod site. The Poldhu transmitter was completed by the beginning of September 1901.

Later in September, the Poldhu antenna collapsed during a heavy gale and a simpler fan-type antenna was built to replace it. In November, the Cape Cod antenna collapsed and, because of the anticipated reduced range of the simple Poldhu antenna, Marconi decided to attempt one-way communication only at a much closer site in Newfoundland rather than rebuild at Cape Cod.

By mid-November trials were being, held and very strong signals from Poldhu were received at Crookhaven in the South of Ireland.

Marconi sailed from Liverpool on November 26 accompanied by two of his assistants, Kemp and Paget. The receiving station equipment, together with balloons, kites, and other supplies, packed in laundry-type hampers was brought with them. They landed at St. John's, Newfoundland on Friday, December 6.

After comparing different sites, Marconi chose a high hill overlooking the Port. It had a small plateau, some two acres in area, where the kites and balloons could be manipulated when raising the temporary antenna. The Cabot Memorial Tower, designed as a telegraph signal station, stood on a crag on the plateau giving the area its name - Signal Hill.

A hospital had been established on the site in a building formerly used as a military barracks and Marconi was given the use of a room in this building. The room was furnished with a table and a single chair. The hampers were brought in and the equipment unpacked.

On Monday, December 9, the installation was complete and one of the 14 foot balloons was inflated with some 1000 cu.ft. of hydrogen gas and an attempt was made to raise an antenna. High winds, however, quickly snapped the balloon's mooring rope and carried the balloon away.

The Marconi crew, bundled up in heavy clothing as some protection against the bitterly cold weather, struggled with kites and eventually raised an antenna wire to a height of about 400 feet. The kite surged up and down over the sea causing the antenna circuit capacitance to change drastically and unpredictably. Marconi was then forced to use an untuned input instead of his recently patented 7777 circuit. Originally, Marconi had intended to use his modified coherer as a detector with its relay and its Morse recorder but the higher noise level due to the untuned input made him decide in favour of the more sensitive earphone which would provide him with a better chance of recognising signal from noise. Removing the relay from the circuit meant that the "tapper" would no longer operate to decohere the detector, so a self-restoring detector was substituted. This consisted of a small blob of mercury sealed between two blocks - one iron, the other carbon, in a glass tube. This 'sandwich' acted as a metallic rectifier and had been developed for use in Italian Navy equipment by Marconi's friend, Lt. Solari.

Shortly after noon (local time) on the 12th December, Marconi heard the three sharp clicks corresponding to the three dots of the letter S in his earpiece. He handed the earpiece to Kemp, who also heard the signal. Further signals were received at 12.30, 1.10, and 2.20 p.m.

On December 13 the weather deteriorated further and Marconi discontinued his tests and released the news of his success.

For many years after these tests leading radio engineers were puzzled as to what stroke of luck or freak atmospheric condition would enable the long-wavelength used - about 250m - to span the ocean and produce receivable results in such primitive equipment at noon time when the sun is high. A theory that has gained support today is that a harmonic from Poldhu's spark-gap transmitter was reflected and received by the untuned receiver.

The Poldhu site was used with increasingly improved transmitters for long-distance radio communication until 1933, when the station was dismantled. The Marconi Co. gave the site to Britain's National Trust. An enscribed stone column has been erected, but little else now remains to show the significance of this remote spot.